Houses in Japan depreciate like fish at market: the less fresh, the less it’s worth. As noted by economists, Richard Koo and Masaya Sasaki:

“Houses… last only about 30 years on average, effectively making them a durable consumer good, whereas in Western countries a house is a capital good that will retain its value almost in perpetuity as long as it is properly maintained. The market value of Japanese houses falls even faster than they can be depreciated for tax purposes; after 15 years the typical house is worth nothing.” [1]

Japan, in effect, figuratively and literally trashes about 4% of the annual total GDP on housing [2]. With the aging of Tokyo’s sprawling suburbs, many houses become abandoned and the heirs of the properties are either unwilling to live so outside the central city or unable to pay the cost of demolishing the homes. Though the quote, “Tokyo could end up being surrounded by Detroits” by a Japanese real estate expert can sound like hyperbole, in all, there are about 8 million, and counting, unoccupied homes across all of Japan [3].

Yet with its shrinking population and having three times fewer people, Japan builds as many new houses as the United States [4]. In Japan, there is a preference for having something brand new, not because a previously-owned house is worthless, but no one wants to live in a “used” home [5]. Instead, if it can be afforded, a Japanese tend to hire an architect to design one’s “life-long”, brand-new, and often novel-looking dream home.

This has afforded all aspiring young Japanese architects to design, accumulate impressive portfolios, and outright experiment with architecture. Simultaneously, as the product of such experimentation is always subjectively tied to the owner during his or her lifetime, it is not always guaranteed that the subsequent generations will retain, maintain, and much less live in those structures. A once-in-a-generation architecture consistently has to contend simultaneously with its spectacular debut and inevitable destruction. On the other hand, at a more competitive rate, there is always the option of a catalog made-to-order prefabricated homes; a part of lucrative machination that is operated by the mass-produced residential housing mega-corporations.

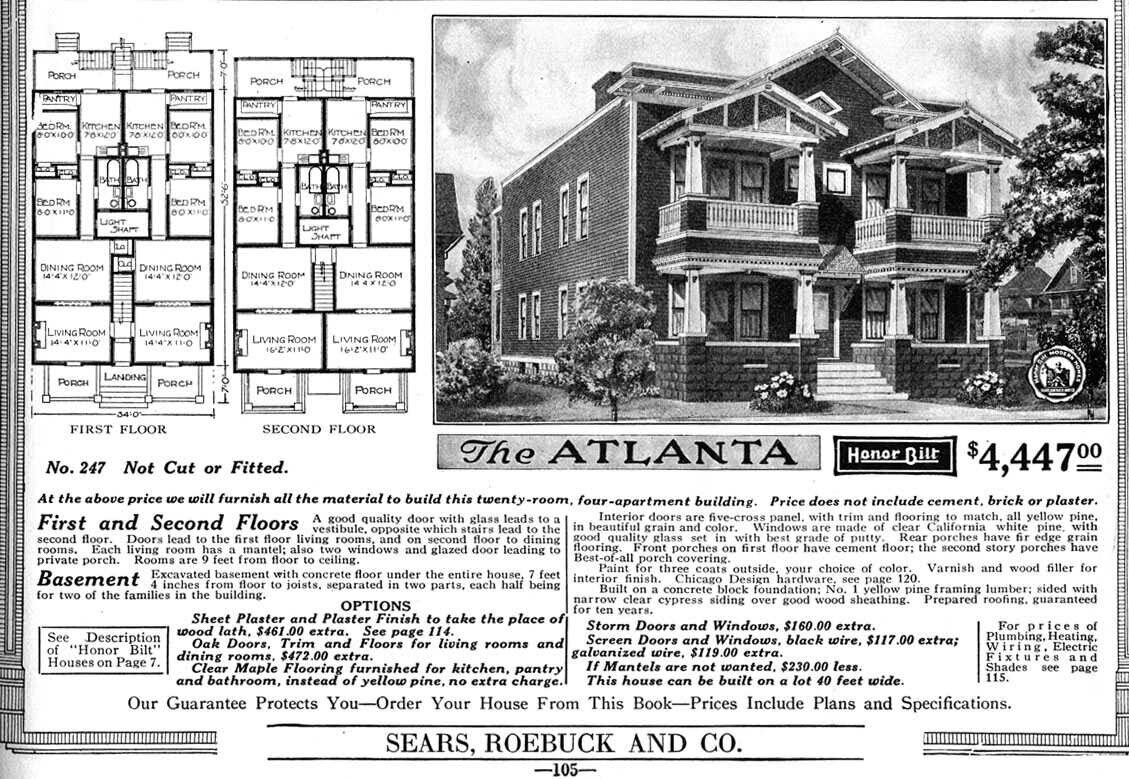

Japan, though notionally still a nation of universal middle-class values, long ago dropped any pretense that a home is any more than a consumer item—“conventional, convenient, disposable” [6]. For the ultimate Sears catalog homes on steroids, Muji has been leading for more than a decade the charge in premium ready-made homes, and “has become not only an internationally renowned company, but for many people is a way of life." Or in other words, “Less and less are we buying products (material objects) that we want to own; increasingly we buy life experiences, experiences of sex, eating, communicating, cultural consumption. ... We are becoming consumers of our own lives” [7]. (To be continued in next month’s edition.)

Thank you for your time and kind attention in continuing to read our newsletters. Stay tuned for next month!

English Writing: Kaz Yoneda & Gregory Serweta

Editing: Mai Tsunoo